Main|Bio|Books|USA Today columns|Opeds|Boston.com blog|Media|Other Publications| Speaking|Links

The myth of the mass shooting epidemic

The risk of being gunned down in public or in school

is overstated.

As a

result, weíre getting bad policies that make us less safe.

By James Alan Fox Updated January 3,

2025, 3:00 a.m.

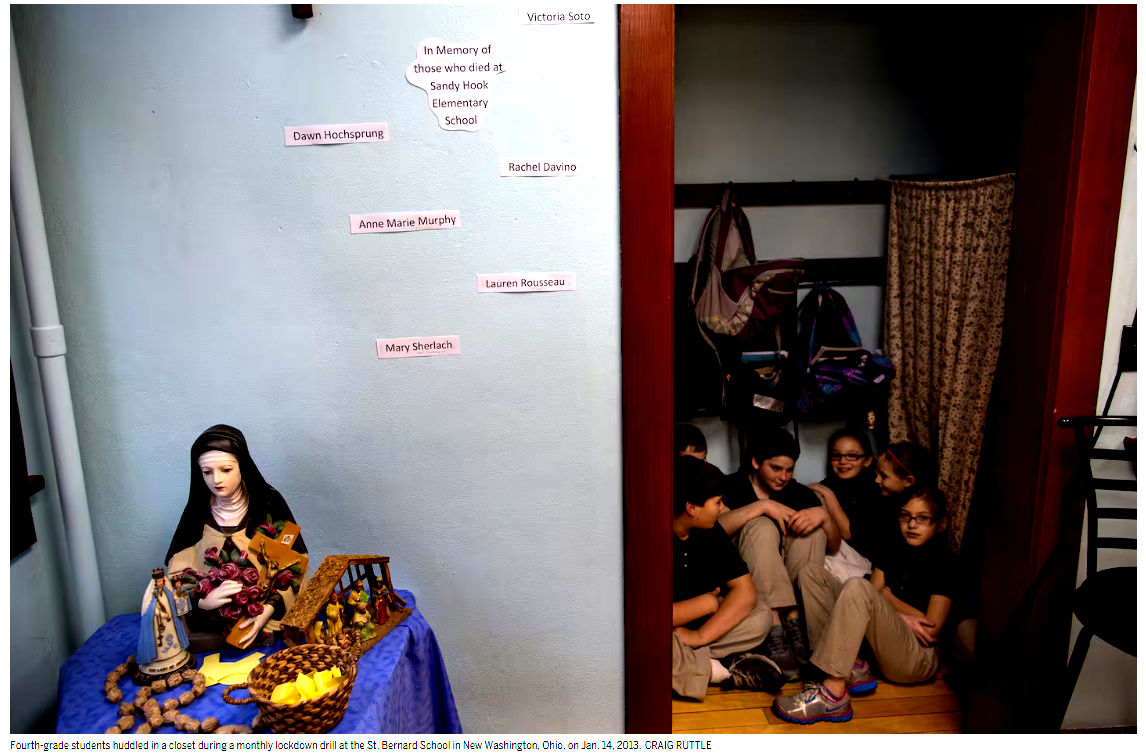

Fourth-grade

students huddled in a closet during a monthly lockdown drill at the St. Bernard

School in New Washington, Ohio, on Jan. 14, 2013.CRAIG RUTTLE

It

may come as a surprise that mass shootings, particularly those in which multiple

people were killed, declined in 2024. According to a database managed by

Northeastern University in partnership with the Associated Press and USA Today,

there were 30 shootings that left four or more people dead last year, down from

39 in 2023.

Even more noteworthy, there were just three such

shootings in public settings: a market in Fordyce, Ark.; a commuter rail train

outside Chicago; and a high school in Winder, Ga. There were 10 such incidents

in 2023.

Deadly public and school shootings are undeniably

horrific. Nevertheless, it is important to keep the risk in proper perspective.

The indiscriminate public slaughters that scare people the most - the ones that

can happen to any of us at any time, in any place, without warning - are far

rarer than we are generally led to believe.

And the high level of fear of

deadly mass shootings is leading to bad policies, from relaxed concealed-carry

laws to traumatic lockdown drills in schools.

Of course, last yearís drop in

mass shootings does not make a trend. The decline came after a year that had the

most such shootings on record. It may just be a case of criminological gravity -

what goes up eventually comes down - and not the start of safer days ahead.

Even so, deadly mass shootings

have not skyrocketed over the past couple of decades, as many people believe,

especially considering the growth in population. It is not an "epidemic" - a

characterization frequently heard in the aftermath of massacres such as the

October 2023 shooting deaths of 18 people in Lewiston, Maine.

But what could be described as

an epidemic are the worry and anxiety, which greatly exceed the risk. The

percentage of Americans indicating that they are fearful about mass shootings

nearly tripled from 16 percent in 2015 to 46 percent in 2024, according to the

Chapman University Survey of American Fears. And as many as one-third of

respondents in a 2019 survey commissioned by the American Psychological

Association admitted to having avoided certain places or events out of concern

for falling victim in a shooting rampage.

In fact, domestic and gang- or

drug-related shootings account for the majority of mass shooting incidents.

A Flourish chart WebSite

So why the sense that these

deadly shootings are rampant when the total number of deaths is in the hundreds

among a population of more than 330 million? In part, it results from the

extensive media coverage of shootings at schools and in other public places.

News coverage of any given

massacre is understandable, but it tends to be accompanied by confusing

statistics. As it happens, there are several definitions of what constitutes a

mass shooting, and depending on which definition one chooses, there may be, on

average, as few as six or as many as 600 mass shootings a year.

Some media outlets prefer the

broadest definition with large incident counts, referencing the Gun Violence

Archiveís tallies of shootings with four or more killed or injured (which also

declined by more than 20 percent in 2024 from 2023). There are hundreds of such

cases every year, but half do not involve any deaths and another quarter result

in a single victim fatality.

I do not mean to overlook the

pain and suffering of those who survive bullet wounds. But shootings that cause

injuries are being conflated with those resulting in multiple fatalities.

For example, at the end of

2021 The New York Times published what it called "a partial list of mass

shootings" that year. The story presented descriptions for "an incomplete list"

of two dozen massacres, each with at least four victims killed, noting that the

list left out "many more." However, the "many more" not listed were several

hundred shootings of lesser severity. In effect, the "partial list"

characterization misleadingly implied that the omitted incidents were like the

deadliest featured in the piece.

Another misimpression arises

with school shootings. In August 2023, according to Gallup, nearly four out of

10 parents indicated that they feared for their childrenís safety at school.

Itís understandable why

parents are so concerned, given some of the statistics reported on school

shootings. "In 2024 there were at least 205 incidents of gunfire on school

grounds," according to the advocacy organization Everytown for Gun Safety,

"resulting in 58 deaths and 156 injuries nationally."

Of this total, 146 involved

K-12 schools, a startling figure. And apparently half of these (76) involved an

attack by an armed assailant, as opposed to suicide attempts, accidental

discharges of firearms, and instances involving no injuries whatsoever. Two

dozen of the attacks left at least one victim dead.

However, the majority of these

fatal assaults happened at school, such as in the parking lot or on school

grounds, rather than in school. Indeed, in 2024, only five fatal attacks took

place within the walls of a K-12 school building - the kind of incidents that

have motivated school districts to stage active shooter drills, allow staff

members to be armed at school, and equip classrooms with door locks and safe

rooms.

These in-school shootings resulted in 11 fatalities in

2024, five of them students. Although one student fatality is one too many, this

was out of 50 million enrolled, translating to a 1-in-10 million risk.

In other words, some of the billions spent by school

districts on "target hardening" might be better invested in school psychologists

to deal with the underlying causes of student angst and alienation rather than

the most extreme outcomes. Moreover, physical security measures, as well as

frequent and aggressive lockdown drills, should be toned down to avoid

inadvertently sending the message to students that they are likely to be in

grave danger while in school.

It is a shame that so many

Americans feel the need to avoid public places when the risk of being gunned

down in them is exceptionally small. It is also sad that a majority of students

feel uneasy at school when they are rather safe there, given the supervision and

structure at school that many youth lack in the after-school hours or even at

home. Itís also unfortunate that some states have reacted to school shootings by

allowing weapons on college campuses, where depression, alcohol, and guns are a

dangerous mix.

Meanwhile, about 20 percent of mass killings are

committed with knives, blunt objects, fire, or motor vehicles, as in the New

Yearís Day attack in the French Quarter of New Orleans. Victims of these attacks

matter just as much as those dying from gunshot wounds. Thus, in addition to

implementing sensible gun laws, we should emphasize prevention strategies that

help individuals struggling emotionally or socially, to address the underlying

causes of extreme violence, regardless of the weapon used.

The right

solutions

Though mass shootings do not

constitute an epidemic, they still deserve our efforts to curtail the already

low risk.

When I said in 2019 that there is no evidence of a

mass shooting epidemic, President Trump retweeted my claim, presumably to deny

the urgency for additional gun restrictions. However, research by my colleagues

and me has found that states with permit-to-purchase laws - including

Massachusetts - have significantly fewer public mass shootings. And states with

bans on large-capacity magazines - also including Massachusetts - have

significantly lower numbers of casualties when there is a public shooting.

A lesson from the

not-too-distant past reminds us that we are actually safer when we spend less

time and mental energy worrying about such tragedies.

From February 1996 through

March 2001, the nation was shocked by eight mass shootings in schools, each with

at least four victims and two or more fatalities, including the Columbine High

School massacre of 1999. A contagion of bloodshed developed: Dispirited

adolescents took their cue from other young assailants before them. The scourge

of gun violence was of such concern that the Clinton administration convened an

advisory committee on school shootings, of which I was a member.

But after March 2001, mass

shootings in schools stopped. There were none for another four years.

Apparently, there was a shift in what weighed on the minds of Americans.

Following the Sept. 11 terrorist attack, the nation became hyper focused on

threats from abroad, and the contagion of school shootings faded. For a while,

angry or miserable students were not thinking that shooting up their school was

a thing to do.

Again, none of this is to diminish the terror of

massacres and school shootings. But it is to say that they should not be viewed

as our "new normal."

James Alan Fox is a professor of criminology, law,

and public policy at Northeastern University and coauthor of "Extreme Killing:

Understanding Serial and Mass Murder." He oversees the Associated Press/USA

Today/Northeastern University Mass Killing Database.

Actual Article Link:

https://www.bostonglobe.com/2025/01/03/opinion/mass-shootings-gun-violence-epidemic/?s_campaign=8315:varf