Main|Bio|Books|USA Today columns|Opeds|Boston.com blog|Media|Other Publications| Speaking|Links

This year there have

been zero public deadly mass shootings

Mass shootings are a serious problem but not an

‘epidemic.'

By James Alan Fox May 12, 2025 at

6:15 a.m. EDT Today at 6:15 a.m. EDT

A memorial to the victims of the Apalachee High School shooting in Winder,

Georgia, last year. (Audra Melton for The Washington Post)

When it comes to crime statistics, bad news is big news. But to make sound

policy, we need to hear good news, too, like the recent decline in mass

shootings.

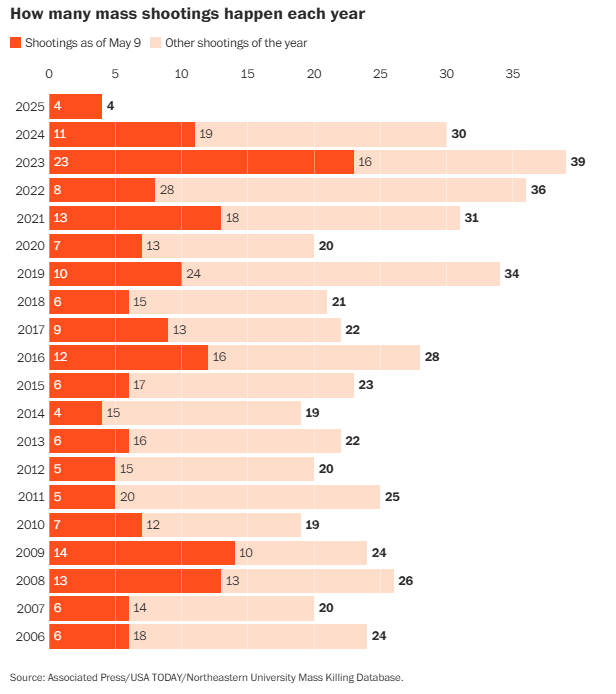

As of May 10, there have been four shootings in the United States in

which four or more victims died this year, compared with 11 at the same juncture

last year. It’s the lowest incident count over the first four months of a

year since at least 2006, when researchers started the Mass Killing Database,

which is maintained by the Associated Press, USA Today and Northeastern

University

The drop builds on year over year data, which shows that mass shootings declined from 39 in 2023 to 30 in 2024.

A similar pattern has emerged for mass shootings with fewer or no fatalities.

According to the Gun Violence Archive, shootings with at least four victims

killed or wounded declined from 659 in 2023 to 503 last year, a 24 percent drop.

By May 10, the numbers plunged further, from 152 last year to 106 this year.

Of course, the heartening although short-term trend over the last 16 months does not guarantee safer days ahead. In 2023, America experienced the highest number of deadly mass shootings on record. It may just be a case of criminological gravity — what goes up eventually comes down.

Even so, the drop underscores an often-misunderstood fact about deadly mass

shootings: They have not skyrocketed over the past couple of decades, especially

considering the growth in population.

Leading outlets have referred to a mass-shooting “epidemic,” particularly when

covering the kind of massacres that rock the nation. These events cause

widespread terror, after all, they can happen to anyone, at any time, at any

place — without warning.

The percentage of Americans indicating that they are fearful of mass shootings

nearly tripled from 16 percent in 2015 to 46 percent in 2024, according to Chapman

University. And as many as one-third of respondents in a

2019 survey commissioned by the American Psychological Association

admitted to having avoided certain places or events out of concern for a

shooting.

The truth is these events are exceedingly rare. Moreover, nearly half of all

mass shootings take place in private dwellings, and about one-quarter involve

gang conflict, drug trafficking or other criminal enterprises.

Last year, three mass killings involving firearms occurred in public settings —

at a

market in Fordyce, Arkansas, a commuter train outside

Chicago, and a high school in Winder,

Georgia. That was down from a record of 10 the previous year. So far

this year, thankfully, there have been none.

High anxiety has led to bad policy responses in the aftermath of these

tragedies, from relaxing concealed-carry laws to staging traumatic lockdown

drills in schools, neither of which has been shown to reduce the risk.

The media can help ease fears by more accurately covering the issue. That

includes reporting not just upticks, but downticks, as I am doing here. It also

means distinguishing non-deadly mass shootings from those that claim the lives

of many people. Gunshot wounds matter and sometimes are debilitating, but death

is different.

To question, as I do, the notion that mass shootings are an epidemic does not

deny that they constitute a significant problem in the United States. Our nation

is home to about 4 percent of the world’s population yet

accounts for between 16 percent and 26 percent of public mass

shootings, the very type of incidents that Americans fear. Easy access to

high-powered firearms and large-capacity magazines are significant contributors.

Research I’ve conducted with colleagues shows, for example, that states

requiring permits to purchase firearms have significantly fewer public mass

shootings and those that maintain limits on magazine size have fewer casualties

when there is such an incident.

Crafting effective prevention strategies requires calm deliberation, not

ill-conceived quick fixes in the immediate aftermath of bloodshed.

James Alan Fox is a professor of criminology, law,

and public policy at Northeastern University and coauthor of "Extreme Killing:

Understanding Serial and Mass Murder." He oversees the Associated Press/USA

Today/Northeastern University Mass Killing Database.

Actual Washington Post Article:

WashPost5.12.25ZeroPublicShootings